History

Native Youth Congress Inspires and Empowers Future Conservation Leaders

to Embrace Tradition and Honor Cultural Values

When Addressing Social and Environmental

BY ALEJANDRO MORALES, PUBLIC AFFAIRS SPECIALIST MIDWEST REGIONAL OFFICE

July is a month that so many celebrate summer with sun, sprinklers, picnics, and fireworks under the night sky. After July 4th, Native American high school students from across the country gathered to consider a big question, “As future leaders, how can you use your voice and skills to make a difference for the environment, while continuing to respect your culture and strengthen your sovereignty?”

These native youth leaders were taking part in the Native Youth Climate Adaptation Leadership Congress at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s National Conservation Training Center in Shepherdstown, West Virginia.

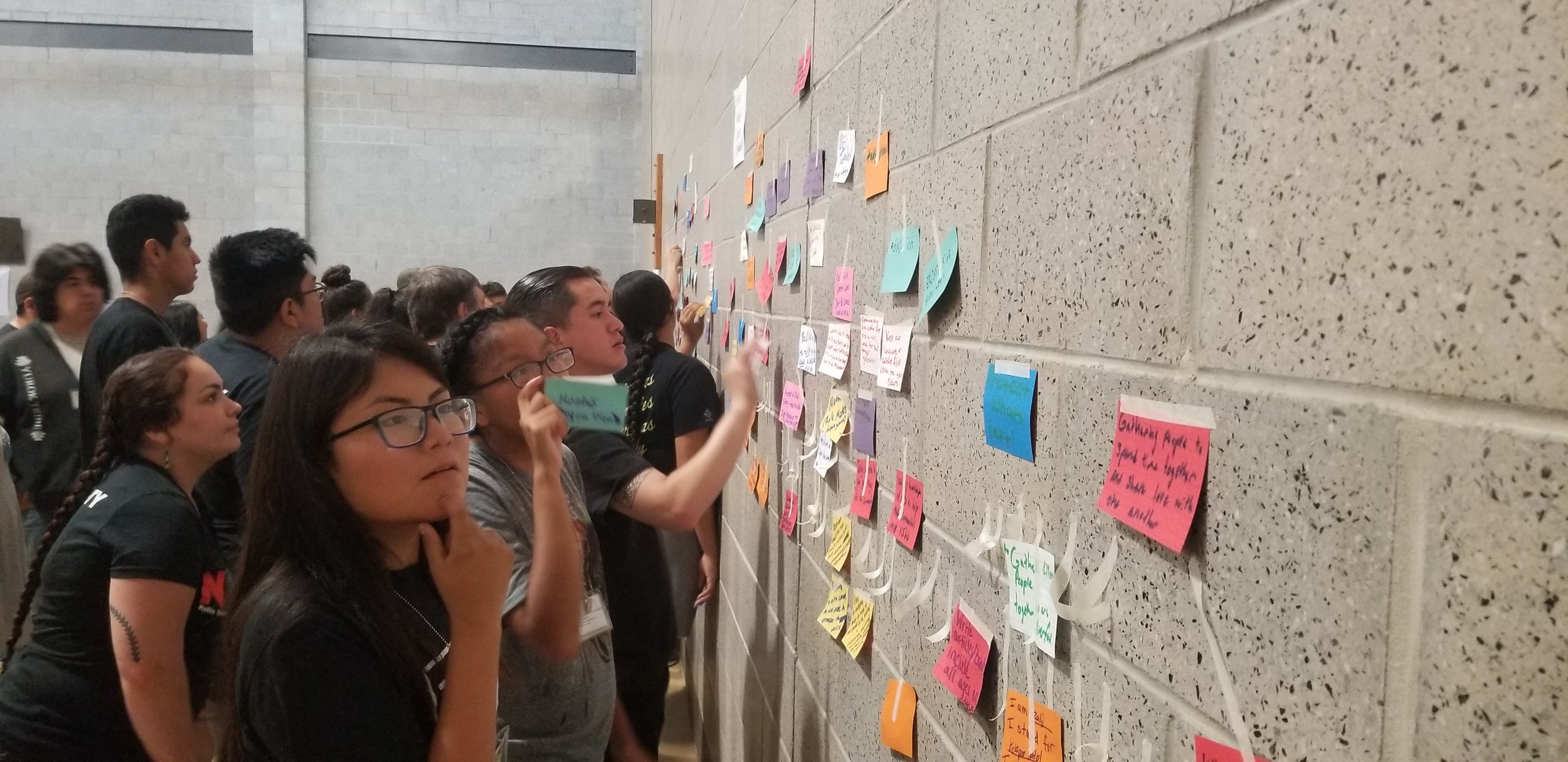

Student participants add their responses to the big question to a wall to get a comprehensive understanding. Photo by USFWS.

While exploring culture, tradition, and science to answer the big question posed at the beginning of the week, students led the congress and focused on major challenges in their communities. The students created themes based on their initial answers to the big question. These themes emphasized the importance of language, elders, political involvement, traditional values, cultural preservation, and social-economic and environmental awareness.

The native youth leaders worked in groups to create a project that covered the theme or challenge they wanted to take on. At the end of the Native Youth Congress, each group presented responsive ways to overcome the selected theme. No one project was the same, but held unique indigeneity crafted from generations of tribal knowledge. For example, one group reenacted a traditional story with each youth leader playing a role, groups even used an iPad to create and edit hilarious sketches that posted to YouTube, while others took the grassroots movement approach to start social change like Billy Frank Junior and Winona LaDuke. Inspiration for projects came from whole cloth, but nonetheless each group inspired each other and re-sparked passion in a few Native American speakers that inspired the student’s days earlier.

This Native Youth Congress wanted to ensure these future conservation leaders did some traditional learning and the native students participated in habitat restoration service-learning projects, outdoor environmental workshops, an interactive scavenger hunt and career fair, and provided cultural one-on-one interactions that resembled traditional tribal teachings.

“Each activity fostered culture and opportunities for students to share their thoughts, traditional knowledge, and cultural values on conservation. Indigenous knowledge and the native way of life has helped tribal communities adapt through countless challenges,” said Jennifer Hill, Project Lead Coordinator, “We developed the native youth adaptation congress to reflect their identity, empower their future and show tribal youth that government is no longer trying to kill the Indian – but trying to support tribes and the next generation of conservation leaders”.

The goal of the congress is to help aspiring native youth to be conservation leaders interested in learning leadership qualities and embrace adaptation skills to address environmental challenges facing their tribes and communities.

Student participants prepare their group project by interviewing one another. Photo by USFWS.

“The Native Youth Congress allows for many students to come together and express their cultural values and to allow youth to put themselves in a situation that they may have never been before,” says Devon Parfait, Geophysics Student at Williams College. “I’m seeing students learn adaptation skills and in turn, I’ve heard discussions about how to use their tribal knowledge in new ways.

For many congress participants, environmental responsibility, conservation legacy and adaptive resilience are well-integrated within their traditional practices and cultural values.

“I came here as a sophomore in high school, and I wasn’t aware of the climate challenges that was happening in native communities,” says Jaycee Owsley, Fisheries and Biology Student at Humboldt State University. “Coming to the youth congress has been an eye opener, it’s showed myself and other students how we can be leaders in our communities by honing our skills in technology, communication and science to take home to our communities.”

Historically underserved, the Native American demographic has often viewed federal agencies negatively. As federal agencies work to rebuild trust, the Native Youth Congress fosters a positive exposure to representatives from the Departments of the Interior, Agriculture, Aerospace and Defense. Community resilience and native youth engagement are important components of U.S Fish and Wildlife Service and the Bureau of Indian Affairs priority of supporting tribal sovereignty.

By the end of the Native Youth Congress, many of the students gained a better understanding of what challenges they faced, and which were a priority for their community. Students unanimously agreed they all faced environmental change and shared how to integrate adaptive solutions to address those changes. Future native leaders have learned which federal agencies support their them and will work to ensure a healthy, natural environment for their communities, many of which are heavily dependent on wildlife, fish and plant populations their traditional practices, subsistence lifestyle and the foundation of their economy.

Student participants prepare their group project by interviewing one another. Photo by USFWS.

Efforts to keep native youth engaged and interested in being future leaders do not end with the Native Youth Congress. For now, participants in the Native Youth Community Adaptation and Leadership Congress serve as informed voices, building environmental change awareness and incorporporating adaptive resilience strategies within native communities for the continuing benefit of tribal people and the public.

“At the beginning of the Congress, not all the students may fully understand the impact and value they bring,” said Rachael Novak, Bureau of Indian Affairs Resilience Coordinator, “At the end, students want to go home and influence their tribal communities, help their leaders become engaged, and share new ideas to get friends back to the outdoors. The confidence in their knowledge, identity and skills as leaders is evidence that tribal resilience is strong. It’s also great to hear students also consider the government as a future career option after seeing the Indigenous federal faculty there working to help Native communities.”

The Native Youth Climate Adaptation Leadership Congress is possible thanks to our following partners, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Reclamation, Environmental Protection Agency, Federal Emergency Management Administration, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. National Park Service, South Central Climate Science Center, U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service and U.S. Geological Survey, and New Mexico Wildlife Federation.

Special Thanks to Melissa Castiano and Jamie Stoner